“If we consider performance as of disappearance, of an ephemerality read as vanishment and loss, are we perhaps limiting ourselves to an understanding of performance predetermined by our cultural habituation to the logic of the archive? [...] in privileging an understanding of performance as a refusal to remain, do we ignore other ways of knowing, other modes of remembering, that might be situated precisely in the ways in which performance remains, but remains differently?” (Schneider 98)

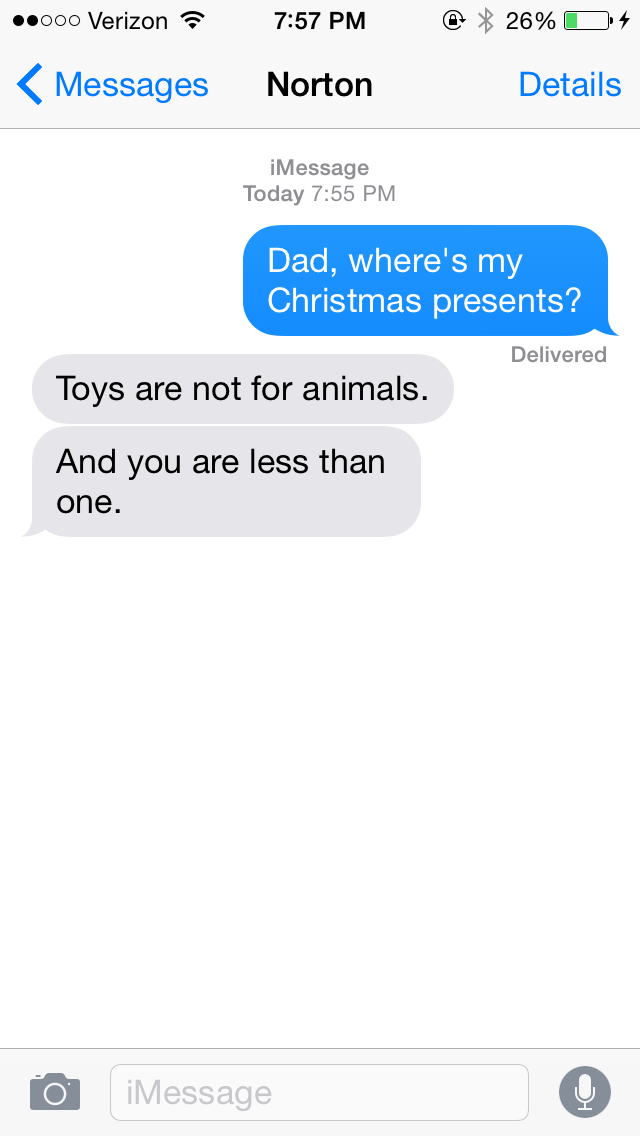

In thinking about the Schneider article, we were struck by the idea that there might be a way to resist vanishing, and what it would mean to read a kind of text that has perspectival ephemerality--i.e. that one person views as naturally disappearing, but another saves for an archive of sorts. One of the more current examples is Snapchat, but we decided to dig up some 2009 goodness and give you Texts From Last Night, from Woman on the Edge of Time and The People in the Trees.

From Woman on the Edge of Time

From The People in the Trees

I dig this use of ephemera. One issue I had with Schneider's article is that she never seems to deal with the role of ephemera in the archive -- it's there, neatly labeled as such in file folders, waiting to be discovered. How would y'all define ephemera anyway? It seems like it too resists neat categorization as strictly "other".

ReplyDeleteI really love the way you thought through vanishing or resisting it by engaging with current forms of social media that ideally allow us to exist in the cloud without leaving a footprint (which seems in practice to be nearly impossible (think of the nude photos hacked and leaked from celebrities clouds). Also, I burst out laughing at "dafuck is this?! babies, obvi," which is horrifyingly hilarious. This is a very cool use of media to investigate Schneider.

ReplyDeleteI really like this look at the line between texts that one person (the author!) assumes will be thrown away but someone else will think is worth saving. Our culture has a lot of "throw-away" compositions, including text messages, tweets, and Facebook statuses--but there are groups of people conscientiously composing archives of everything ever tweeted, among other texts. And these archives will likely be used in the future for historical and social studies. It makes me wonder if we would write differently, if we were more conscious that our writing isn't going to just vanish. And, if we did, how would that change future scholars' perceptions of us?

ReplyDeleteAlong with Jess and Bethany, I thought your connection between Schneider's discussion of ephemerality and the resistance of ephemerality through saving and publishing text messages was very creative. I never would have thought of that! Your version of "Texts from Last Night" and the concept of resisting disappearance reminds me of the reading app/program Spritz, which flashes words on the screen as a method of reading, thereby making archived texts vanish, in a way. It's hard to explain Spritz, so why not just go to their website and experience it: http://www.spritzinc.com/. Of course, Spritz doesn't actually make texts vanish from existence as you read them, but as words flash up on the screen and are quickly replaced with other words, I can't help but feel anxiety about the fact that the words are disappearing before my eyes, and that I can't go back and reread, or view an entire sentence at a time as I can with most other literary texts. But despite the ephemerality of reading vanishing words, Spritz claims that readers often have better comprehension and retention when they read via Spritz than via linear reading.

ReplyDeleteI wonder how Spritz might connect with your reading of Schneider's article?

The comments about ephemerality and archivability made me wonder about what happens when the archives themselves disappear. I suppose nowadays everything that makes it to the Internet is stored in multiple places, much to the despair of persons who post things they wish they hadn't - like the GOP staffer who chose to take the Obama daughters to task this weekend and who is now looking for a new job. So ideally everything should be recoverable. But if we think pre-Internet and we consider the literary archives that have been lost through willful or natural destruction, we grieve knowledge now devastatingly irrecoverable. I especially mourn the destruction of the library in ancient Alexandria--whether deliberately burned or the victim of a succession of unintentional fires, we now know that the loss of so many unique manuscripts impeded the progression of many disciplines, mathematics, science, and medicine to name only a few. The scene haunts me--what was lost, what will never be known, what knowledge could have redirected history if it survived? I suppose that the Internet will prevent such permanent losses in the future; ephemeral objects themselves might disappear but the content they contain will be forever retained. Unless, of course, we lose the Internet…but that could never happen, right?

ReplyDeleteI had not considered that now-obvious crossover between ephemera collecting and digital-widgetal cloudy-woudy stuff. Bethany's question is a fascinating way into that terrifying shadowy space. Digital confetti: not necessarily retained on purpose but rather through inertia, more like a hoarder's close-ish-to-the-trash-bin pile than a safe or even a drawer stash. What the heck. How are our future fans going to encounter our Selected Letters? Not for them the ribbon-bound stack of yellowed cursive-covered pages. Nope. Texts about meeting for a beer, and six separate emails from my mom about the video of a cat in a shark costume riding a robot vacuum cleaner. And they're worried that we think Margery Kempe was a nut??

ReplyDeleteBrining it back with texts from last night! I really enjoyed this post, and wonder if what you did might count as deconstruction. I feel a faint trembling... But seriously I'm curious if anyone else read Schneider's gesture of reinserting (re-doing, etc.) her old piece from 2001 as an odd form of auto-deconstruction. It made me think about deconstruction and performance, their differences, their relationship, and the limits of each. What is gained/what is lost when we perform a text? What is gained/lost when we deconstruct it? My initial response is that performance might be a deconstruction in a given time/space, and the ephemerality of performance is ultimately a saving grace for the text, what prevents it from being permanently destabilized. This is something we take for granted in the creation of another text in writing deconstruction.

ReplyDeleteFollowing Briana, Jess, and Sally's commentary: In the age of digital media such as texts, emails, tweets as presumed ephemera vs. state, university, or corporate-sanctioned preservation, how might we read the archive as menace? That is, those who are not so digitally savvy might presume that their texted video of a cat riding a Roomba is *not* preserved for posterity, but corporate digital preservation and the Cloud tell us otherwise. What if the archive is a threat?

ReplyDeleteOf course, the archive HAS ALWAYS ALREADY been a threat...discuss...

Delete